*** Latest update: 10th Feb 2021 ***

Hey there! My name is Aimee Spinks and I’m an award-winning unit stills photographer. If you have landed on this page and are interested in hiring me to cover your production, head on over to my unit stills portfolio here.

For those of you here because you want to learn about being a stills photographer or maybe how to get into the industry yourself, keep reading!

I often receive requests for interviews, phone calls and general advice from aspiring photographers looking to start their own careers in the film industry. I like to give as much back as possible; after all, without the generosity of their time from unit still photographers such as Jay Maidment or David Appleby, I may not be in the position I am today to help inspire the next generation of shooters.

As I can no longer keep up with giving personal responses to each and every request I receive, I thought it would be helpful to write a blog post collating some of the most frequently asked questions that come in, and answering them as best I can. If you have questions you cannot find the answer to in this blog post, please email them to me as I will periodically add to this post.

I also plan to publish a book which elaborates further on many of the points raised in this post and explores more of the business end of things such as:

- How much do unit stills photographers charge?

- How to negotiate with a client to get the terms you want whilst maintaining positive working relationships.

- What contract terms you should look out for so you don’t get ripped off.

- How to structure your rate card so you don’t have any nasty surprises when you take a job.

- How to charge for poster shoots and why these are different to shooting unit stills photography.

- More detail about equipment such as:

- What specific items I use for tricky situations.

- Key accessories to make the job easier.

- Things to remember when insuring your equipment.

- What to consider when taking your kit abroad so that it doesn’t end up lost or damaged in transit.

- An exclusive downloadable template of my own rate card for you to use when quoting clients so that you never undercharge again.

If you are interested in checking out the book when it is available, simply drop your details here. As well as keeping you updated there will be opportunities for you to request specific content that you’d like to see included.

Alternatively, if you can’t wait and you really want to kick start your own career as a unit stills photographer and would like to discuss arranging a personalised 1:2:1 mentoring session to help get you to where you want to be in your career, just drop your details into this form and I’ll be in touch!

The following questions are some of those that regularly come in and they often ask both about my own personal experience and career journey as well as more general advice on how to start and maintain a career as a unit stills photographer. As a result, this article and the subsequent book will be mix of points covering both. I have tried to separate out sections with headings to help you identify the bits you might be most interested in.

Finally, one last caveat before we begin; please note that this article reflects my experience in the UK film industry and that other considerations may apply for this nature of work in other territories, particularly North America which is heavily unionised and subject to different expectations. It is also important to be aware that unit stills photographers are self-employed and will therefore have their own unique ways of working – my answers are not the only answers to these questions so do be sure to research the other unit photographers out there and ask for their perspective.

With all that out of the way, let us begin!

What is unit stills photography?

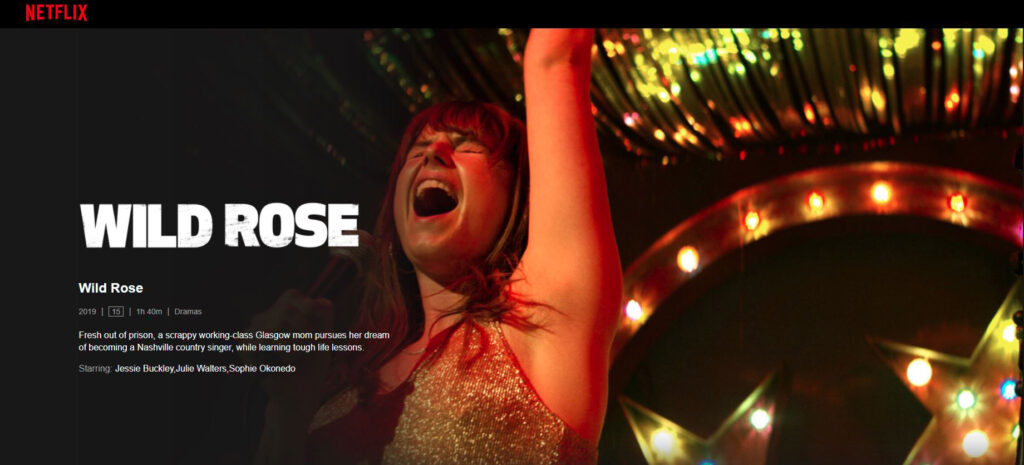

Unit stills photography is photography that provides the images used in the PR campaigns of feature films, TV shows and commercials. The images that you see when trying to decide what to watch on Netflix? A still photographer took those. The photos accompanying articles in Entertainment Weekly, The Hollywood Reporter and Total Film about the latest movies? You aren’t seeing screen grabs (though in the occasional instance you might be); a still photographer took those too.

A unit photographer, also called a set photographer or still photographer, works alongside the filming crew and seeks to capture still images of the action being filmed, as well as behind the scenes photos of the production underway.

What about posters and billboards?

Our unit stills photography also sometimes ends up on billboards, posters and DVD covers, though these photos are often taken during a separate studio shoot, called a specials, gallery, or marketing shoot, rather than taken from images shot on set during filming, and productions sometimes bring in separate advertising photographers to carry out this work, much to the chagrin of the still photographer. More on this further down.

Working as a unit still photographer is challenging and hard work, but the payoff is that you get to work with some of the best creative teams in the world and create images with their stunning set designs, incredible costuming and unbelievable lighting. I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to work with some of the best production crew in the world and know that without their amazing talents, my images would not be the same.

It is, however, a somewhat closed industry with few resources available that can give a clear insight of what the work entails or even how to get the work in the first place. Though there are fantastic initiatives in the UK such as Screen Skills, that seek to find work placements for trainee film crew across many aspects of production, still photography isn’t one that features this opportunity, largely due to the nature of the work. Unlike other departments, you are typically a one-person team, so a production needs to know the person they are placing in that role knows what they are doing.

Unfortunately, this becomes a bit of a chicken and egg scenario; you need the experience to get the work, but you can’t get experience without being hired to do the work. Or can you? I often get asked by aspiring photographers how to get started in the film industry, what does a stills photographer do day to day on set, what are the challenges we face, and a myriad of other questions, so I wanted to take the time to answer some of the most common questions I get asked so that it can hopefully provide some insight for those looking for information on how to start a career as a set photographer.

When did you want to be a unit stills photographer?

My personal story starts at Blackpool and the Fylde Arts College where I earned a 2:1 degree in photography (I’m adamant I was robbed of a first because my lecturer didn’t approve of the fact I was finding commercial clients for my uni projects but that’s a rant for another time) and it was during my final year that I happened to stumble upon the role of a unit stills photographer whilst researching cinematic photography: I was, and still am, a big fan of Gregory Crewdson’s work and I wanted to create a series of images that looked like they could have been taken from a film.

This planted a seed that grew to be my desire to be a movie stills photographer and I spent the first year after graduating working part-time in a portrait studio that taught me to shoot fast and not waste time duplicating shots – once you’ve got it, move on and create something entirely new.

When I wasn’t at the studio, I attended local filmmaking groups and networked both online and at industry events to find no-budget projects to work on. These ranged from film competitions like the 48 Hour Sci fi Challenge, student projects, ultra-low budget shorts and independent features where everyone was working for bus fare and pizza.

These experiences gave me the time I needed to learn how to shoot around a camera op, frame out booms and finally learn to stop tilting my camera to try and make a boring shot look more dynamic. Pro tip: if you need to tilt your camera to make the shot look interesting, it’s not an interesting shot and you should either find something else to shoot or figure out how to tell the story another way.

Your plan for success should never be reliant on the success of others. If it is, make a new plan!

Take control and be bold.

As creatives, we are often very self-critical of our own work. This is great in the sense that it pushes us to constantly learn and develop our skills but it can also undermine our path to success if we lack the confidence to put ourselves forward for big jobs. I had just this problem.

I had the mistaken attitude that if I kept working on these ultra-low/no budget gigs, those producers and directors would eventually work on bigger things and seek to employ the photographer who helped them out time and again. Thankfully, my then boyfriend now husband, Andrew, had a business degree and a whole lotta confidence and he pointed out that it was pretty foolish to pin my hopes of success on the possible successes of others.

He told me to be bold and so, feeling way out of my depth, I started contacting publicists, broadcasters and producers of actual proper productions as well as getting in touch with established stills photographers whose work I admired, to see if there were any opportunities to shadow them or even just buy them lunch over which I could ask endless questions.

How do you get a job as a unit stills photographer?

After ridiculous amounts of my emails going unanswered, I knew I had to be creative and persistent about how I got in touch with people. I tried everything; social media, LinkedIn, bribes of coffee and cake and a never-ending number of trips to London on the 3-hour slow train because I was too broke to get there any other way, sometimes just to have five minutes with a picture manager on their cigarette break. Literally.

I remember one trip to a certain company whereupon my collection from the lobby, the lady I had come to meet told the receptionist to tell her 2:05 appointment to come straight in when they arrived. My appointment was scheduled at 2pm and had required a 6-hour round trip with the last of my disposable income for the week.

That first year was not fun. It was hard. But it paid off. You roll the dice enough times, eventually, you get a 6 and my 6 came in the form of the head of pictures at ITV (Pat, you LEGEND) and Jay Maidment who is one of THE best and nicest stills photographers on the planet.

Pat gave me my first proper TV gig shooting stills for the series Beowulf, and Jay not only gave me a lot of mentoring and advice but was kind and trusting enough to ask me to cover for him on a day of Guardians of the Galaxy which was an opportunity that absolutely staggered me. I grabbed it with both hands and suddenly found myself with a foot in the door.

Who are your clients and do you need an agent to be a unit stills photographer?

Typically, you will be hired by a producer, publicist/publicity firm or the photography team of the network/studio so research who these companies and people are and make sure they know who you are and what value you bring to them.

Personally, I have never had an agent and it’s not something I am looking for. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, I have only ever come across one agent who specialises in unit stills photographers; Barbara Lakin who is based out in Los Angeles. All the other agents I looked into who specialised in representing film crew had little to no experience working with unit photographers. This meant that they were unfamiliar with our role, the process of hiring us, and our rates so the only thing they were bringing to the table were their contacts in the industry.

To join one of these agents would cost, on average, 10-20% of your earnings which for me, is too steep of a price to pay for things that I could learn to do myself. Some agents even take a cut of jobs your find and secure yourself which is not something I’m prepared to agree to.

I’ll admit that at one point I was tempted to try and seek representation from Barbara Lakin in order to establish a presence overseas, however, in the years since I’ve ended up forging my own contacts in the States and learned to have the confidence and skills to approach prospective clients and negotiate with them myself.

I recommend using an agent if you don’t have the confidence or marketing skills to find clients and negotiate contracts or if it’s generally just a part of the job you hate and want to outsource. You may also benefit from working with an agent to begin with so you can establish yourself more easily and learn what to charge from someone who knows how to get a good rate for you but once you have a good foundation in the industry, you’ll likely find jobs come to you and you know what to charge.

If you decide to go it alone, there are some really great sources to check regularly for work opportunities and I use many of them to this day to help me see which productions are starting up and who I need to contact to pitch my portfolio. I’ll include a full list of them in the book version of this blog.

If you are interested in checking out the book when it is available, simply drop your details here. As well as keeping you updated there will be opportunities for you to request specific content that you’d like to see included.

Alternatively, if you can’t wait and you really want to kick start your own career as a unit stills photographer and would like to discuss arranging a personalised 1:2:1 mentoring session to help get you to where you want to be in your career, just drop your details into this form and I’ll be in touch!

If you don’t have an agent, what other skills and personal development should you do to help you secure work?

I’m a big believer that learning should be something you continue to do throughout your life and it’s easier than ever before with the availability of eBooks, audiobooks, online workshops, courses and government backed initiatives to develop business skills.

I’m probably going to mention this a lot but my number one recommendation would be to read or listen to “Never Split the Difference,” by Chris Voss.

Voss is an expert negotiator; in fact, he headed up the FBI’s hostage negotiation team, and now uses his skills to provide top-notch consultancy and negotiation training for the biggest corporations in the world with the biggest deals on the table.

In his book, you will find incredible insights into his time with the FBI, examples of hostage situations and the techniques used to overcome them, and then how you can apply those same techniques into your everyday interactions whether it be negotiating a work contract, convincing people to meet with you and check out your work or resolving interpersonal conflict, all in a way designed to get you your desired outcome whilst also making sure to maintain good relationships throughout the process.

I use the skills found in this book almost every day and it is incredible how positively it impacts your ability to network, build working relationships and negotiate with clients. You can also find Voss on Masterclass which is another excellent learning resource I recommend.

Other areas of personal development I recommend investing in are sales and marketing; learning things like the psychology behind what makes people stop, look and buy; how asking certain questions or phrasing things a slightly different way can influence your likelihood of closing a client; and what simple things you should do be doing online to build your brand, your reach and your credibility.

The book, Traction, by Gabriel Weinberg, is a great place to start if you need inspiration on how to get yourself seen and there are hundreds of high-quality educational podcasts and YouTube channels dedicated to sharing sales skills.

In addition to these business orientated skills, it’s always good practice to keep ahead of your own game so be sure to keep up to date with the latest photography news, gear and trends and brush up on your shooting and editing technique regularly. FStoppersand Phlearnare great resources on YouTube for this.

Another great YouTube channel I recommend is that of unit photographer, Jasin Boland. Jasin is one of my favourite unit photographers of all time and on his channel he hosts conversations with some of the best shooters in the industry like Hopper Stone and Justin Lubin. These guys know their stuff and have been in the industry for far longer than myself so go check them out and give their videos with Jasin a watch – I learned so much from their candid discussions and I’m grateful to Jasin for providing this platform for others to learn from.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWq1PxWtO7M

How much do unit stills photographer charge?

This is a big question which I cover in-depth in my book. In it you’ll find answers to questions such as:

- How much should I charge as a unit stills photographer when I first start out?

- How do I negotiate with clients to get the rate I want if they low ball me?

- Do I need to charge for editing and travel?

- How and what do I charge for poster shoots?

- What’s a buyout and when and how much do I charge for it?

- Why should I never offer half day rates?

- What is equipment rental and how much do I charge for it?

- What other things should I factor into my pricing?

- What contract terms do I need to look out for?

- How and when does a unit stills photographer get paid?

With each copy of the book, you’ll also receive a free download of my rate card template to make it easier for you to present your prices and terms to your clients. If you’d like to know when the book is available, don’t forget to add your details here or get in touch if you want to speed things up and schedule a mentoring session

How do you deal with rejection as a photographer? Did you get rejected a lot at the start of your career?

In the early days there was so much rejection and it all boiled down to one thing; credibility. Why would a big production take a risk on someone new to the industry, fresh out of uni and without any credits or credible experience? That was the nut to crack.

The nut became visible with the best rejection I ever had from Pat at ITV; he said, ‘Aimee, I love your work; you’re clearly a really good photographer, but I can’t pitch you to the producers of my shows unless you have recognisable faces in your portfolio.’

‘I can’t pitch you to the producers of my shows unless you have recognizable faces in your portfolio.’

Head of pictures, ITV

Now, you can choose to take rejection personally and be defensive about the things said to you, keeping you trapped in the same process or way of doing things, or, you can be grateful for the feedback because now you know what to do to improve.

It was a real ‘ah-ha’ moment and so I spent the next few months searching out low/no budget shorts with actors who were on the telly; faces that Pat and his producers would recognize. After I had a few in my portfolio, I went back to ITV and was offered the job of shooting stills for Beowulf.

Do you need to go to university or do a course to be a professional photographer?

Yes and no. Do you need a piece of paper that says I have learned how to take photos? No. What you do need is technical know-how, exposure to the work of incredibly talented photographers for inspiration, and time to experiment. Doing a university course gives you these things, but you can also get them all for free using the internet and devoting a significant amount of time to your own self-development.

If you’re the kind of person who struggles with self-driven learning then a formal course may be a good route to take. However, a degree isn’t the only option open to you; you could invest in a tutor or book yourself onto some workshops to find someone to be accountable to so that you stick to your goals.

Another option is to find a high-quality YouTube learning channel like Phlearn and block out certain times of the week to study and practice a skill from one new video per session. There is so much great practical learning content out there, that regardless of your level of disposable income or free time, there are resources to help you develop the skills you need.

Ultimately, the way you learn is up to you but I can count on one hand the number of people who have asked if I studied photography at uni; most just want to see my portfolio for reassurance that I know what I’m doing.

Speaking of portfolios…

What images should I include in a photography portfolio when first starting out?

As I mentioned a little while back when you approach new clients for the first time, if you don’t already have a track record in the industry, you need to build credibility so that they can trust you to deliver the goods.

Unfortunately, that means they are probably going to spend more time looking at who you are shooting, rather than the overall quality of your work (ridiculous, I know).

Obviously, make sure the images in your portfolio are technically and artistically good, but you need to also spend time getting recognisable faces into your work. So, ask yourself; what can I do to enable me to have the opportunity to point my lens at someone people know? Then go out and do it.

Being self-employed you need to have a can-do, solution-oriented attitude so I’m not going to give that answer to you on a plate; consider it a test of your problem-solving skills – you’re going to need them in the job.

Still on the subject of portfolios, I recently got asked this question:

Do you have any advice for building a portfolio? Is it better take on any opportunities that come your way or to identify the kind of genre of work you would like to do early on?

When you first start out as a unit stills photographer, you’re going to be taking every opportunity that comes your way as each new job, even if it’s just a day covering the main photographer, exposes you to more people, builds your experience and adds to your portfolio. That said, it is worthwhile being selective with your portfolio as soon as you can.

After doing a handful of gigs with Channel 5 on live entertainment shows, comedies and factual TV, I realised these were the jobs I had zero interest in. They paid the bills at the time and I loved the picture editor I was working with (hey Chris!) so I kept doing them when they came my way but I only very briefly put them in my portfolio.

I love sci-fi, action, horror, period drama and thrillers as these are often the genres that are most visually interesting to me; I therefore decided to only put images in my portfolio that fit these kinds of things. It meant that for a long time my portfolio was very sparse, so why did I do this?

I wanted people to hire me for the jobs I wanted: if prospective clients see my photography portfolio and it’s a mish-mash of everything, I’ll probably attract a mish-mash of work. If they come to me and only see stills of period drama, they will associate me with those kinds of shows and so though they may not consider me for the comedy series going into production that week, they will think of me for the period drama that starts up a month later.

In-line with this kind of thinking, when you are just starting out, you are likely to be taking on a range of work – not just unit stills – in order to make a steady income. In the early days I took on fashion work, corporates, headshots and even weddings to help pay the bills, however, I had a separate website and brand identity for each.

They were just basic WordPress sites like this one, but it meant that if a wedding client came to my website, they saw I was a wedding specialist, the same way that if a fashion client came to my website, they would see I was a fashion specialist. This approach increases both client confidence in what you do as well as sales, not just through the added credibility that comes with being seen as a specialist but also user experience of the website itself; they see exactly what they came looking for with pricing, information, images and calls to action specifically in line with what they want.

It is for this reason that I very strongly recommend having a separate website that focuses on unit stills if this is the avenue you want to go down.

But you still have sections of your website on actor headshots? Do you still do this kind of work and does it not contradict your last piece of advice?

The split of my work at the moment is 90% unit stills photography & 10% actor headshots photography. I decided to keep both on my site for a few reasons; firstly, they both complement each other and are part of the same industry. Secondly, I’m at a point in my stills career where I can be working almost full time on a film or TV project for several months. At the end of it I usually want a month off back home as working as a unit stills photographer requires long hours and lots of time away from home, family and hobbies.

Being able to line up actor headshots which is work I enjoy, are done locally to me, and usually only take a couple of hours of time in the day, is a nice way to keep a bit of money coming in whilst still giving me lots of downtime.

I particularly enjoy shooting actor headshots as it’s a whole other way of working that I’ll probably write a blog on someday. Having my headshot work on my unit stills website shows film clients I know how to shoot portraits and it excites my headshot clients to know that they have had their headshot taken by someone who has photographed actors like Samuel L. Jackson, Eddie Redmayne and Margot Robbie.

Can you use all of the images you’ve taken in your portfolio?

Yes and no. Under no circumstances should you digitally share any images from any production that has not yet aired/been released. This includes putting them on your website, social media, giving out crew shots or emailing images as part of a wider portfolio to a new prospective client. If you want to share images digitally you must wait to see which images your client releases and use these.

One of the most frustrating things as a unit photographer is when clients do not release the best images from a job, especially the images that are golden portfolio material and even more so when you are new to the industry as you can sometimes be forced to wait 12-18 months before you can release the images that are going to really help you get a foot in the door.

Waiting for images from Guardians of the Galaxy to be released was agonising – I could tell people I had done some work on it but I couldn’t show them anything until the official release came about 18 months after I took the photos. Even then I didn’t know if they would use one of my shots.

You said yes though too? Correct. Once a production has been aired and the release window passed (this is the window of time where the movie/show is still being heavily marketed to increase audience size), then put together a contact sheet of the images you would like to include in your portfolio and email them to your client to ask permission to put them in your portfolio. Most of the time they will say yes, however, it may also be dependent upon talent approvals (we’ll get to that shortly).

Another way for you to be able to show your best work when it matters is in face to face meetings as you will be able to bring a hard copy of the images (either in print or iPad/tablet format) that you can then take away with you. This is also a great way to convince potential clients to meet you – it’s the only way for them to get an exclusive look at your best work and face to face meetings are much more likely to result in you getting work than relationships built via email alone.

Do I need a website for unit stills photography?

Yes. 100% yes. Invest in a good website. Make sure you have plenty of pages and text to make your site show up in searches and ensure your image files aren’t too big as this will cause loading delays which in turn increase the likelihood of people clicking off your site.

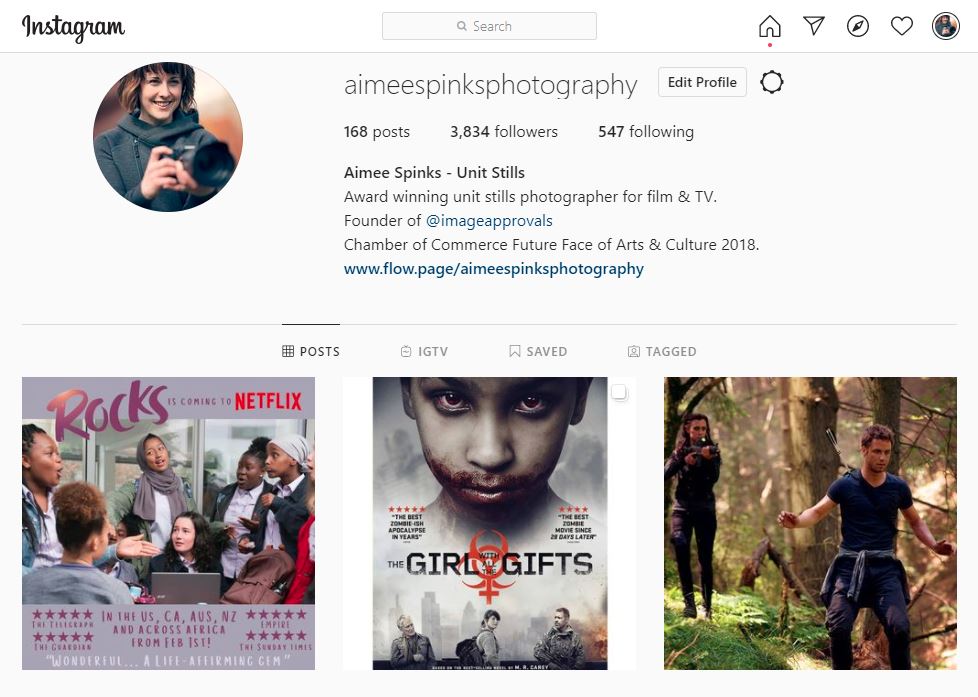

I also recommend maintaining a strong presence on Instagram; it’s a great visual platform to showcase your work, engage with the industry and demonstrate your reach by cultivating high numbers of good quality followers. Some photographers also claim to have been hired via clients seeing them on IG so consider using it if you don’t already.

Maintaining a strong social media presence takes a lot of work and there are lots of strategies worth knowing about to help increase engagement so I highly recommend doing some research into social media marketing. Scheduling platforms such as Later and Hootesuite are great tools to use as they enable you to schedule posts in advance across multiple social media platforms at a time so check them out if the thought of posting online every day doesn’t appeal to you.

What inspires you and your work?

I am inspired by the work of other unit and specials photographers such as Jay Maidment, Jasin Boland, Jaap Buitendijk, Johnathan Olley, Giles Keyte, Hopper Stone and Aidan Monaghan who are brilliant and very well established unit photographers. It’s always a good idea to see what kind of work the most in-demand stills photographers are producing to see what clients are wanting.

I also try and find inspiring documentary and fine art photographers so that my work doesn’t just stick to an obvious commercial look when it comes to composition etc. Sure, a lot of commissioners want this, but I want to differentiate and be seen as a photographer who truly understands the art of it and so hopefully attract more of the kind of productions who appreciate this approach. Doing this makes my work stay fresh, challenges me to see things differently and constantly improve my image-making.

I also enjoy working with directors and DPs who have a visual approach that starkly contrasts with my own style as this forces me to look at things in ways I might not normally. I have found I have made my biggest leaps forward when doing this as it forces me to break habits and think creatively.

What equipment do you need for unit stills photography?

My kit has grown over the years and changed with new technology. The advent of pro spec mirrorless cameras like the Sony A9 were a huge game changer and fundamentally changed the kit bags of many set photographers.

When I first started out as a unit stills photographer back in 2011, I went into the industry armed solely with a Nikon D800 and two lenses: a 24-70mm and a 70-200mm, both at f2.8. The other single most important bit of kit that went with this was my Aquatech sound blimp.

As you’ll know, DSLR cameras make a clicking sound when the shutter is pressed and this isn’t acceptable on set where noises can distract actors and make life difficult for the sound department. A sound blimp is a foam-lined box in which you’d place your camera to deaden the sound of the shutter and was required by every photographer in order to shoot during takes. You would also have a different lens tube for each lens which would screw onto the front of the blimp.

Blimps were an absolute nightmare to work with. The original versions didn’t even have a cut out on the back for viewing the monitor, or access to camera controls – you had to have all your settings, including your AF settings all nailed before the start of the take and you wouldn’t be able to change a single thing until the take was cut. It would then be a mad race to open up the blimp, pull out the camera (which was a task in itself as the camera is so wedged in there) to check your shots, change your settings, or if you had lots of time, run and change lens and tube. They weren’t just utterly impractical for shooting but they were huge and heavy, resulting in more than a little back ache. But that was what you needed to have to get the job done.

As my work increased I could afford to buy a second body – a second hand Nikon D3s – and blimp to make it quicker and easier to shoot without the need to change lenses and tubes. Then thankfully, around 2015, Fuji and Sony changed everything with the first line of pro-spec mirrorless cameras to hit the market.

I found myself in a dilemma – do I spend ~£6,000 to stay with Nikon and upgrade to the recently released D4 and get a blimp for it, or, do I embrace new technology, jump ship and start again from scratch with a mirrorless system? Well I am a big believer in adapting quick, so sensing a paradigm shift and the thought of halving the weight of kit I’d be carrying around for 12 hours a day, I dived into bed with Sony. To this day I have zero regrets.

What equipment do I use today?

So what exactly do I have in my kit bag at time of writing (Feb 2021) and what do I recommend to others looking to start out in the industry? First, let me give you a quick overview of my current key items, and then how I break that down and shift it about depending upon the job:

For shooting unit stills photography:

- 2x Sony A9 Camera Bodies

- Sony 24-70mm f/2.8 GM lens

- Sony 70-200mm f/2.8 GM lens

- Sigma 20mm f/1.4 lens

- Sony 35mm f/1.4 GM lens

- Sony 50mm f/1.4 Zeiss lens

- Sony 85mm f/1.4 GM lens

- Sony RX100 V compact camera

- Several spare camera batteries and around 12 of the fastest 32GB Sandisk SD memory cards.

- Various filters, esp circular polarisers and UV filters for each lens size.

- Remote camera trigger

- Laptop and portable hard drive

- Spider Belt

- A small folding stool

- A small folding table

- Wet/cold weather bag:

- Waterproof jacket and trousers

- Rain covers for camera and lenses

- 4×4 poly bag

- Small microfiber towel

- Hand warmers

- Spare socks

- Hat and gloves

- A pop-up tent when working outdoors in bad weather

- A Tipke folding cart

- Various camera bag sizes, including one HUGE bag that will hold everything listed before the small folding table and a smaller one that is airline compliant.

- A large rolling flight case that will fit all cameras, lenses and filters for when I need to take kit abroad and have it placed in the cargo hold.

For camera mounting:

- A selection of Manfrotto magic arms, super clamps and spigots for articulated mounting to different surfaces.

- A suction cup mount for gripping to car windows and other non-porous, flat surfaces

- Tripod.

- Safety cables for securing cameras mounted remotely.

- Camera cage to that the arms and clamps can more easily be attached to the camera.

For specials/poster work:

- 8x Bowens flash heads

- Selection of modifiers including softboxes, parabolics, honeycombs, grids, snoots, gels etc

- Large background support frame

This kit enables me to do pretty much everything I need but that doesn’t mean you can’t do the job without it all.

“You can shoot 90% of most jobs with just one decent low-light camera with two lenses: a 24-70mm f/2.8 and a 70-200mm f/2.8 and you can certainly shoot your first few jobs with nothing but these.”

The rest of the kit either makes your life a bit easier or helps you cope with tricky situations such as low light (which is becoming very common on studio sets now) and rain. Of course, the bigger the production, the more often you will be faced with and be expected to overcome these tricky situations and as you gain experience and pay checks, you’ll want to expand your kit. I, for instance, currently have my eyes on the Sony 135mm f/1.4 lens after working on a couple of particularly low light jobs that it would have been handy to have had a longer prime for.

A good unit stills photographer knows to be as still and as non-distracting as possible during a take and also that you might not be able to shoot from the ideal position. There’s also the chance that something unexpected might happen during a take, and so I usually start each scene on one of my two zoom lenses as these give me the most flexibility.

I generally only bring out my prime lenses if it’s too dark for my 2.8 lenses or, if I’ve covered everything I need safely on my zooms and have a few free passes to play around with a more experimental shot. It’s for this reason I really do believe the best kit to start out with is a good low-light mirrorless body with a 24-70mm and 70-200mm 2.8 set of zoom lenses and that these will in fact enable you to cover most of what you need to get, in the easiest way.

I have several more chapters that really dive deep into equipment including;

- Common problems with some mirrorless cameras that make them unusable for unit stills photography.

- What you need to have and do to make sure you don’t lose images.

- What niche little accessory hacks I use to make the job infinitely easier.

- Why you should avoid second hand and grey market goods.

- How to safely take your equipment abroad without it getting lost, stolen, damaged or getting you arrested for unknowingly illegally importing and exporting it.

I’ll also discuss equipment insurance and highlight some of the common pitfalls some photographers make which can lead to losses or damage that your insurance provider will not cover. These chapters will all be included in my book. If you would like to register your interest in the book, drop your details here and I’ll be sure to let you know when it is available.

What sort of things does a unit stills photographer need to capture?

You always need to remember the purpose of your images; to sell the film. A good still photographer will capture images that show the essence of a scene without giving too much away; character portraits; behind the scene photos of the key cast and crew for use in industry magazines; and archival material such as detail images of props, costuming and set builds – basically anything that fans and media outlets might find interesting and want to show alongside articles promoting the production.

Included in the book is a handy checklist you can use to make sure you get all the different types of shots your client requires. As mentioned above, drop your details here and I’ll be sure to let you know when it is available.

How many images do you shoot in a day?

It depends on the day and what we are covering. Fast paced action will naturally see you shooting more frames than two stationary talking characters. I shoot a lot of period drama and on dialogue days I’ll probably turn in an average of 350 images, maybe going up to around 500 if there is lots of action, crowds of supporting artists or big new sets or locations that need documenting. On a basic dialogue day I might shoot around 500 images in total and then cull out test shots, misfires or any other image that isn’t, in my opinion, good enough to drop straight into a magazine with my name on it.

A good skill to acquire as a unit stills photographer is to know how to get everything you need without over-shooting. Think quality, not quantity. A good exercise to practice is to look at your images as you shoot them and ask yourself, would your client use it? Both in terms of it being a technically good enough shot to use but also in its content – what value or information does this shot bring to the client or viewer?

Something else to consider when deciding how to cull your images before handover is compositing. Sometimes your client might not plan on using the whole image but might want to take elements from one to add into another. If, for instance, you are shooting dialogue between 5 actors who are all gesticulating and making big expressions, I’d recommend shooting and keeping more of these shots so that your client can have flexibility on compositing multiple images together as it can be tricky to have everyone looking exactly right during scenes like this. Also consider background elements – if it looks like it could be useful in compositing, keep it for the client.

Ultimately, I like to make sure I can give the client everything they need without them wasting their time looking through anything superfluous. Don’t be the unit stills photographer who turns in 600+ of the same shot of two people talking because you had your camera set to continuous shooting and couldn’t be bothered to cull them – the production’s publicist will not want to work with you again.

Do you set your shots up or shoot them during takes?

I personally like to get as many of my shots as possible during a take. This is when everything is in place and the actors give it their all. Sometimes, however, you might need to ask for a set-up.

Set-ups are shots you set-up outside of a take. For instance, let’s imagine there’s a shot you really need but there is no space for you to shoot it from because the filming camera is there. If it’s a key image you know is important (and you REALLY cannot get it during a take), then ask the 1st AD if you can switch places with the camera once they have their shot. You might need to stand very ready, very nearby and politely remind the 1st when the time comes and it doesn’t hurt to give the camera operator and grip a heads up of your plans so they know to disappear sharpish once they get the nod – the quicker you can get in and out to do the job, the better.

When your moment comes, be confident in describing to the cast what you would like them to recreate. A good 1st will hold the crew from working/moving around and instruct background artists to repeat their action so you can recreate the scene as closely as possible and get the shot you need. Be aware that you likely won’t be able to recreate the entire scene – pick a very specific moment to focus on and shoot the crap out of it in 30 seconds or less. Thank everyone and vanish so the rest of the team can crack on.

Other examples of set-ups might be character portraits where you find a space either on set at a moment it isn’t in use, or at an appropriate spot as close as possible so as not to take cast too far. Before approaching cast for a set-up portrait, make sure you know exactly what you are shooting and where and that everything is set up and ready to go. You should also inform the actors’ make-up artist and costumier so they can run checks to make sure they are camera-ready.

Do unit stills photographers edit their images?

Clients do not expect you to, however, some photographers choose to. On smaller budget jobs, the client is unlikely to do any retouching on your work before sending it out to publication, so you may decide to do some tweaks before handing them over.

On large shows and movies, the client will typically release a small number of photos which will have been approved by cast and sent to a professional retoucher before they go out so you may decide to do fewer tweaks.

Generally speaking, a set photographer will shoot far too many images to be able to edit them all individually so any retouching done is usually broad stroke editing that can be done in batch via software like Adobe Bridge or Lightroom and focuses on colour and exposure corrections so that the client has a clean image to work from.

The photographer will then typically submit the images in their preferred raw format alongside some low res JPGs to make it easier for the client to view them.

What does your workflow look like?

In the book I’ll walk you through my image processing workflow step by step so you can learn:

- How I edit my work.

- How I structure my workflow so image processing doesn’t take hours.

- File naming and folder conventions to make images searchable.

- How I use rating systems to identify image types.

- How I deliver my work to clients.

- My backup process to prevent any data loss.

Drop your details here and I’ll be sure to let you know when the book is available, alternatively, as writing a book is a very slow and laborious process, if you want to get a head start in your career and book a 1:2:1 mentoring session, get in touch.

What are photo approvals?

Most actors these days have an image approvals clause in their contracts which enables them the right to kill a certain number of images taken by the unit stills photographer. These are negotiated separately by each actor; however, the most common contract terms are that they must approve at least 50% of solo images and at least 75% of all images in which they appear with one or more other actors who also have approvals rights.

As they have the ability to kill images, it is prudent to make sure you have at least a few different shots of the same thing so that cast have the ability to kill images where they perhaps dislike their expression, whilst also leaving the client with some usable options on that particular shot.

Photo approvals are becoming more and more common as the advent of social media means it is more important than ever for actors to retain some control over their image. Traditionally, approvals were done manually by handing the actor or their agent a fat stack of contact sheets and a highlighter. As you can imagine, this is HORRIBLY inefficient, so (plug warning), I partnered with a software development agency to build a digital platform that enables actors to manage their photo approvals online. I rather imaginatively named it, Image Approvals (hey, it’s great for SEO!). If a producer or publicist asks you about managing approvals, just send them that link and they will LOVE you for it, I promise, and so will I.

The other upshot of recommending Image Approvals to a production you are shooting for is when it comes to getting permission to be able to use certain stills in your portfolio. Earlier, we touched on how if you send a contact sheet of images to your client after the release window of the production has passed asking for permission to use them, you might be told no due to talent approvals. It takes effort to cross-check the images in your contact sheet with the list of images contractually approved by cast and it may be work your client is unwilling to do and result in them just saying no.

If they used Image Approvals to manage talent approvals, we can supply you with a list of all officially approved images form that production. This will enable you to remove any killed images from the contact sheet and let your client know that you have checked that the shots you would like to use have all been officially signed off by cast. With any luck, this will result in your client allowing you to use the shot(s) in your portfolio.

Is it scary working with big actors?

At first it can be incredibly daunting but just remember, we are all on set to do a job and great actors understand the value of quality still photography when it comes to selling the film or TV show. Every actor likes to work differently so it’s important to approach them with an open mind to changing how you might want to photograph them. Ultimately the best photography comes when the stills photographer and actor work collaboratively so find out as soon as you can if they are the kind of actor to be chatty with, or the kind who wants their space and respect it.

Always remember to introduce yourself before photographing someone; it is incredibly rude – at least in my mind – not to do so. Better yet, ask the 1st AD or producer to give you an introduction. It can sometimes be tricky to find the right moment but you should make it a point to do so as soon as possible, even if that means coming in early to catch them whilst they are in make-up.

When I first started out, I would get nervous about speaking with big actors and so I developed a really useful tool to tackle it that I still use today whenever I get anxious about something.

It may or may not work for you, depending upon the kind of personal encouragement you need but this works for me personally: the moment I detect that flighty feeling, I decide I must do that which I am nervous about right then and there no matter what. I immediately shut out all other thoughts and go for it. This stops me ruminating on my anxiety which would make it seem scarier than it is. Now obviously you need to use your common sense on just how ‘immediately’ you can act given what is going on around you, but resolve to make it your priority.

Everyone has strong personal values and an identity they see as them. For me it is my integrity and discipline and so I use this against myself in these situations by authoritatively telling myself that I cannot have either of these if I allow myself to be scared into inaction. This may seem a little harsh and be a really unhelpful way of thinking to some people so adjust it to whatever kind of personal encouragement you need; I’m just the kind of person who responds better to a personal trainer screaming at me for blood than one who tells me I’m doing great when I start flagging.

One memory that always sticks in my mind was when I was asked to take some shots of the key cast of The Legend of Tarzan on a day of pre-production camera tests. This was SUPER early on in my career and I had zero confidence.

The publicist introduced me to Margot Robbie and Alexander Skarsgard but didn’t get a chance to introduce me to Samuel L. Jackson before she had to go. Needless to say, I was shitting my pants. Scared, introverted me wanted to just lay low and simply nip in and out to take the shots in between what the camera crew were getting without having to talk to anyone.

However, the part of me that had decided I would never photograph an actor without first introducing myself thankfully took charge, gave me a whole load of mental abuse for being a wimp and gave me the kick I needed to push my way through the half dozen people surrounding the man himself so that I could shake his hand and say hello, literally seconds before he headed in front of the camera and I would have missed my window.

The feeling I got after having done that and seeing how appreciative he was, was incredible and I get it every time I force myself out of my comfort zone and face my fears. When you do it often enough, you soon realise that some of those big scary things aren’t scary at all, and you can start approaching the world with more confidence. So, whenever you get that fight or flight hit of anxiety, instead of associating it with fear, reframe it as a cue to take action.

Which members of crew do still photographers work most closely with?

Building relationships on set makes your job much easier! You absolutely should make the 1st and 3rd ADs your best buddies as these are the people who will facilitate your access to cast. Closely following these are the camera operators, grips, focus pullers and boom ops as they are all likely to be in the exact spot where you want to shoot from. Build trust and respect with these ladies and gents and you’ll find them much more accommodating when you need to squeeze in tight to them!

Another person on set to get to know is the Director of Photography, also called the DP, DOP or Cinematographer. This is the person who decides how the production will be filmed and lit as well as what the final colour grade of it might be. Keep a close eye on the framing choices of the DOP as you should try and keep your stills consistent with their style so that they accurately reflect the production they will be advertising. Working with the DOP will be a DIT (digital imaging technician) who is often hidden away in a van or tent, working with the rushes (daily footage) and applying a quick grade for the DOP to see. Make sure you have a peek at this so you can convey the colour grade to your client.

Depending on the production, you will also likely be working with a unit publicist. This is often the person liaising with you on your client’s behalf, if they are not the client themselves. If you have difficulties on set, the publicist will have your back and can help grease the wheels for you.

What is the most challenging thing about being a unit still photographer?

There are many challenges to being a unit stills photographer. The main one is being sensitive to on set etiquette and being able to instantly read a room. A still photographer is usually the first person to be asked to leave the set if tensions are high or the set is tight so make sure you are not a nuisance and are as invisible and as unobtrusive as possible.

This means making room for other filming crew, even if it means sacrificing your shot, and knowing when is and isn’t appropriate timing to ask for set-ups as these slow down production.

Unit stills photographers must be able to take criticism and rejection well, have you ever been in a position where someone told you they didn’t like your pictures? How did you deal with it professionally without being offended?

So far either the commissioners have liked what I’ve produced or they’ve been too nice to say otherwise! This job is a collaboration so I go into each production with a clear brief and keep communication open with the publicists/photography managers so that they can comment on work as I shoot. This way any tweaks or changes in approach can be discussed and implemented as shooting progresses to ensure everyone is happy with the result.

Yes, this means you’ve got to be open to sometimes changing what you might want to do with your work, but you need to remember that you are getting paid to fulfil the commissioner’s brief, not your own. Ultimately if you ask the right questions and prepare enough going into a production, you shouldn’t have any problem creating work the client loves.

Do you need to be able to use studio lighting as a unit stills photographer?

It depends what you want to do. Many photographers specialise specifically in unit photography, however, productions do usually also need studio portraits in addition to the unit coverage in order to create posters, DVD covers and other advertising material. These are called specials or gallery shoots and are either done by a different photographer who specialises in them, though increasingly unit photographers are also offered the chance to cover the specials if they have the studio experience and equipment.

So yes, having studio experience is an advantage as it gives you the option to cover both and some productions do prefer to keep the same photographer to cover each as they already have a good rapport with the cast and understand the production in depth.

The other upside of having studio experience is that it gives you a better understanding of light and how it is shaped to create different results which can be hugely beneficial when shooting unit stills photography – usually, if you want to pull an actor aside for a quick portrait, you need to do it using whatever light is available, which may not be perfect for what you need. Being able to work with what you have and adapt your approach to get the results you want is a crucial skill to have.

Do you have any advice for a soon to be graduate who is interested in Unit Stills photography?

Find filmmakers to collaborate with and develop your portfolio on their projects. Then it is all about networking and approaching bigger and bigger productions each time. Be persistent with your contacts and don’t be afraid to aim high.

If you have any questions, drop them over in an email and I shall add them to this Q&A!

Looking for more, why not check out my portfolio?